One of the things we have been thinking about since the summer of 2014 is whether or not to label 3D printed objects with Braille. In many cases having a label on the object is confusing, since it might be hard to tell what is surface detail on the model and what is the label. So in many cases we may want to have a detachable label, or perhaps a key for a set of models with just a single letter label or a tactile symbol actually on the object in some specified place. There were also some projects (such as tactile maps) for which it was useful to make Braille labels separately so that they can be changed later (for example, if a building is renamed or repurposed).

Once you decide to use Braille at all, though, one discovers that it is not as easy as it looks. There are various standard ways to have abbreviated Braille and other standards of use issues that take a while to learn. Most fundamentally though, Braille comes in standard sizes, and we are told that odd-sized Braille is confusing. See http://www.brailleauthority.org/sizespacingofbraille/sizespacingofbraille.pdf

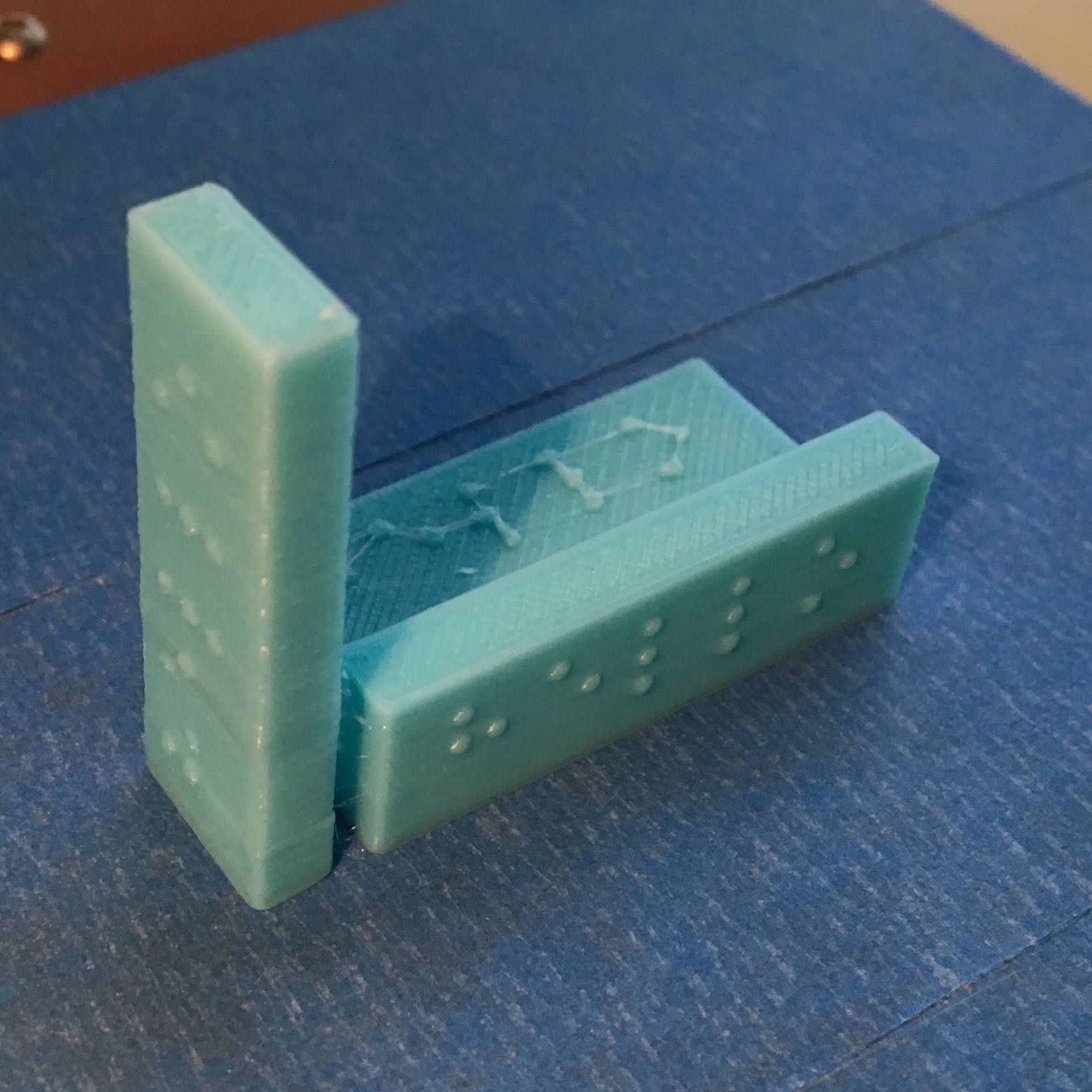

Also, Braille dots are supposed to be domed, not cylindrical, and when [Whosawhatsis] surveyed several blind Braille readers at a conference on using 3D printing for the visually impaired using some Braille samples that he printed, the consensus was that the Braille was easier to read when it was printed on a vertically-oriented surface of the print, rather than on the top surface. Most of those surveyed found the dots printed on top rough and uncomfortable to read (due to layering effects and stringing), while the ones printed on the side were smoother. These will also be less likely to wear and peel off quickly. Here's a sample:

You can find the OpenSCAD files for this at: https://github.com/whosawhatsis/braille-openscad

The ReadMe file describes how to use the OpenSCAD file you find there. It will create a small block like the one in the image above, a little bigger than the one letter. You can import this into another design program as an STL, or you can build the rest of what you have in mind in OpenSCAD, downloadable at http://www.openscad.org.

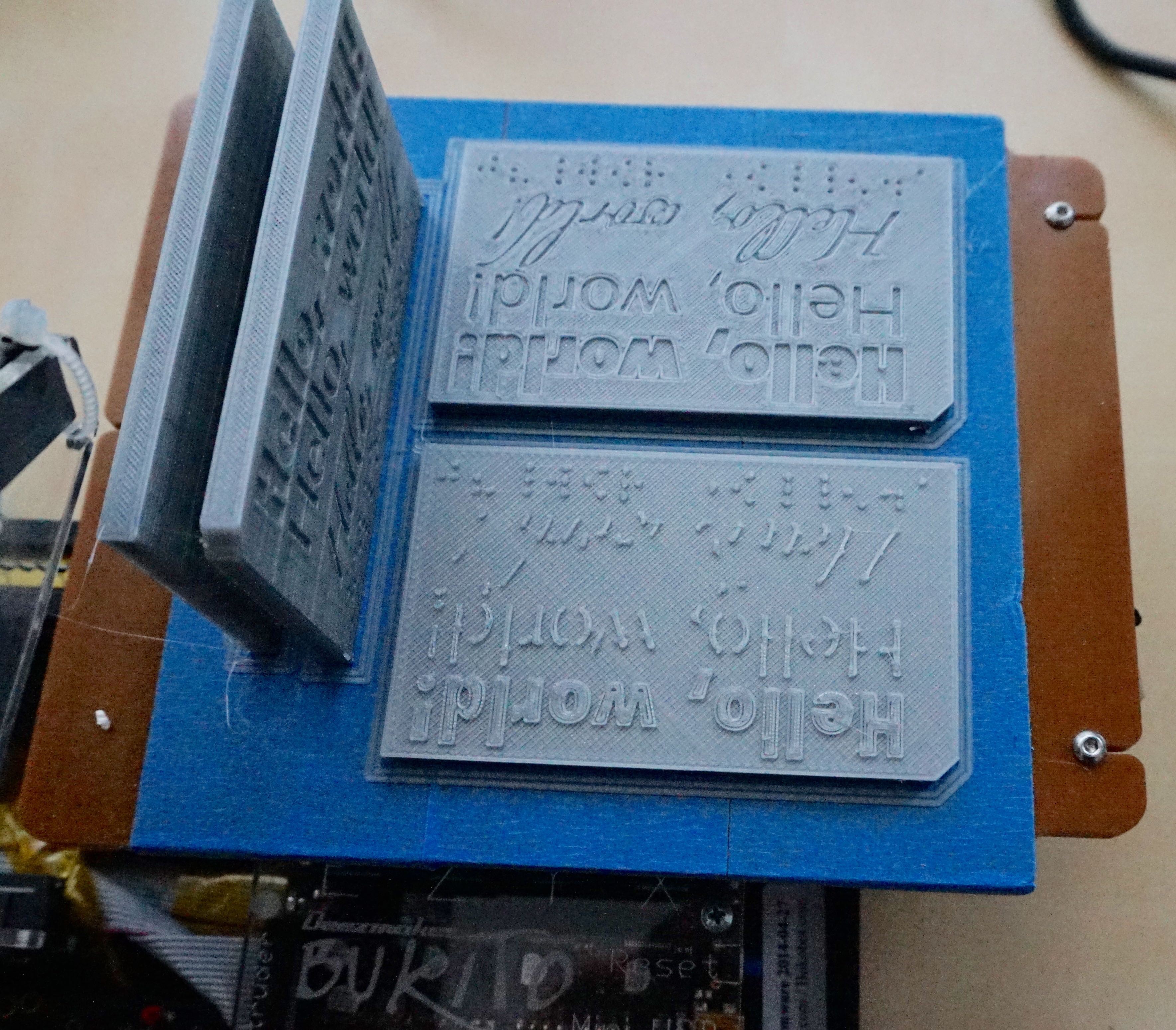

For our 2015 book, "3D Printing With Matter Control," we printed some experiments with both Braille and letters in various fonts, both raised and inset, printed in different orientations. As expected inset letters printed more accurately than raised ones, and inset Braille dots were not readable. In either case, the features were cleaner and stronger when printed on a vertical surface, compared to a horizontal (top) surface,

So we learned that

- Braille on the models themselves should be minimized, except in cases where a label is really part of the model (like a ruler)

- It is important to follow existing standards for dimensions

- If at all possible it should be printed on a vertical or nearly-vertical side

Thanks to the group at the workshop sponsored in summer 2015 by Benetech.org's Diagram Center, the ongoing task force chaired by Jim Allen, and inputs by Lore Schindler of LAUSD, and Mike Cheverie of The Valley School.

Joan Horvath

Joan Horvath

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.