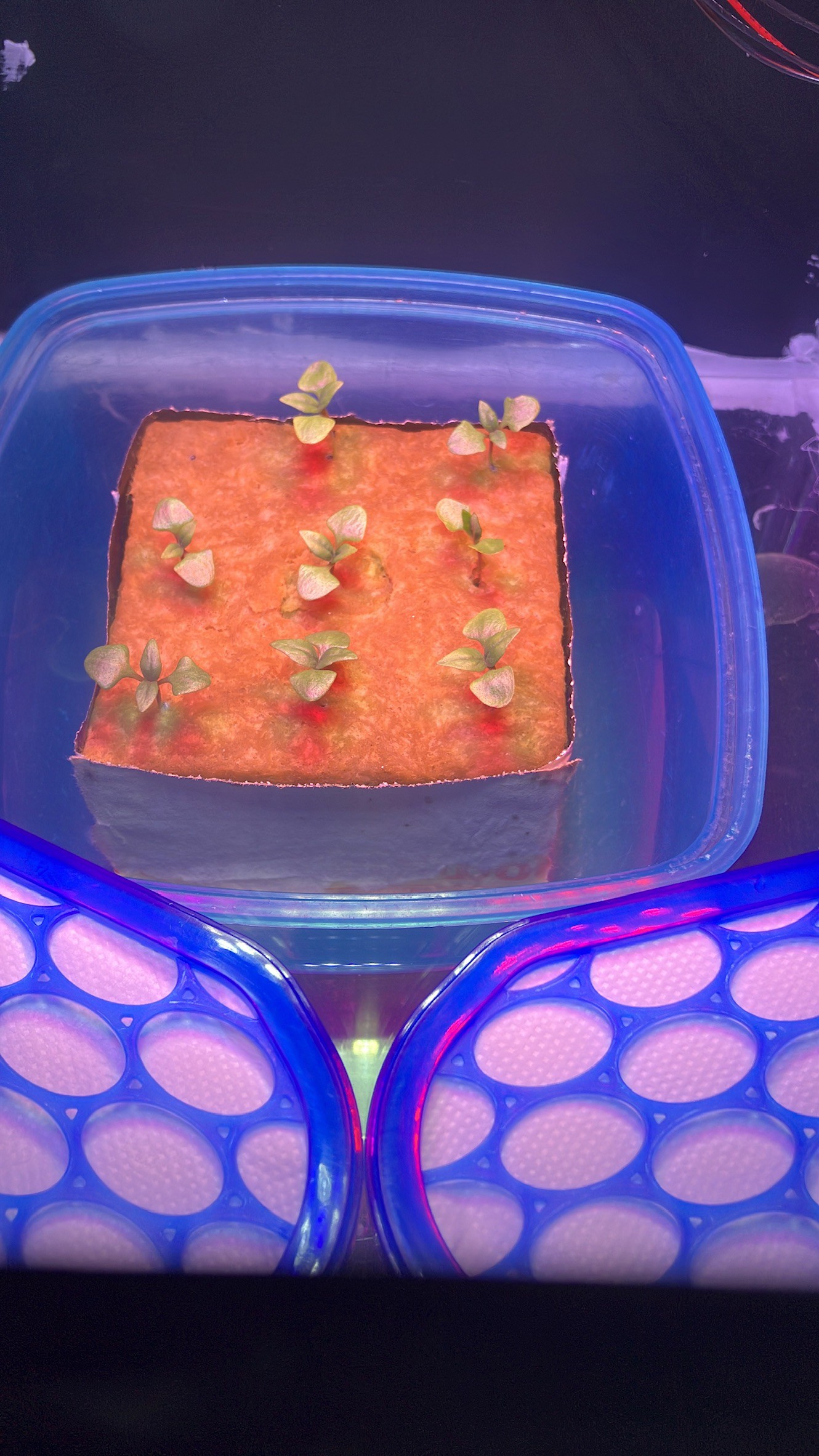

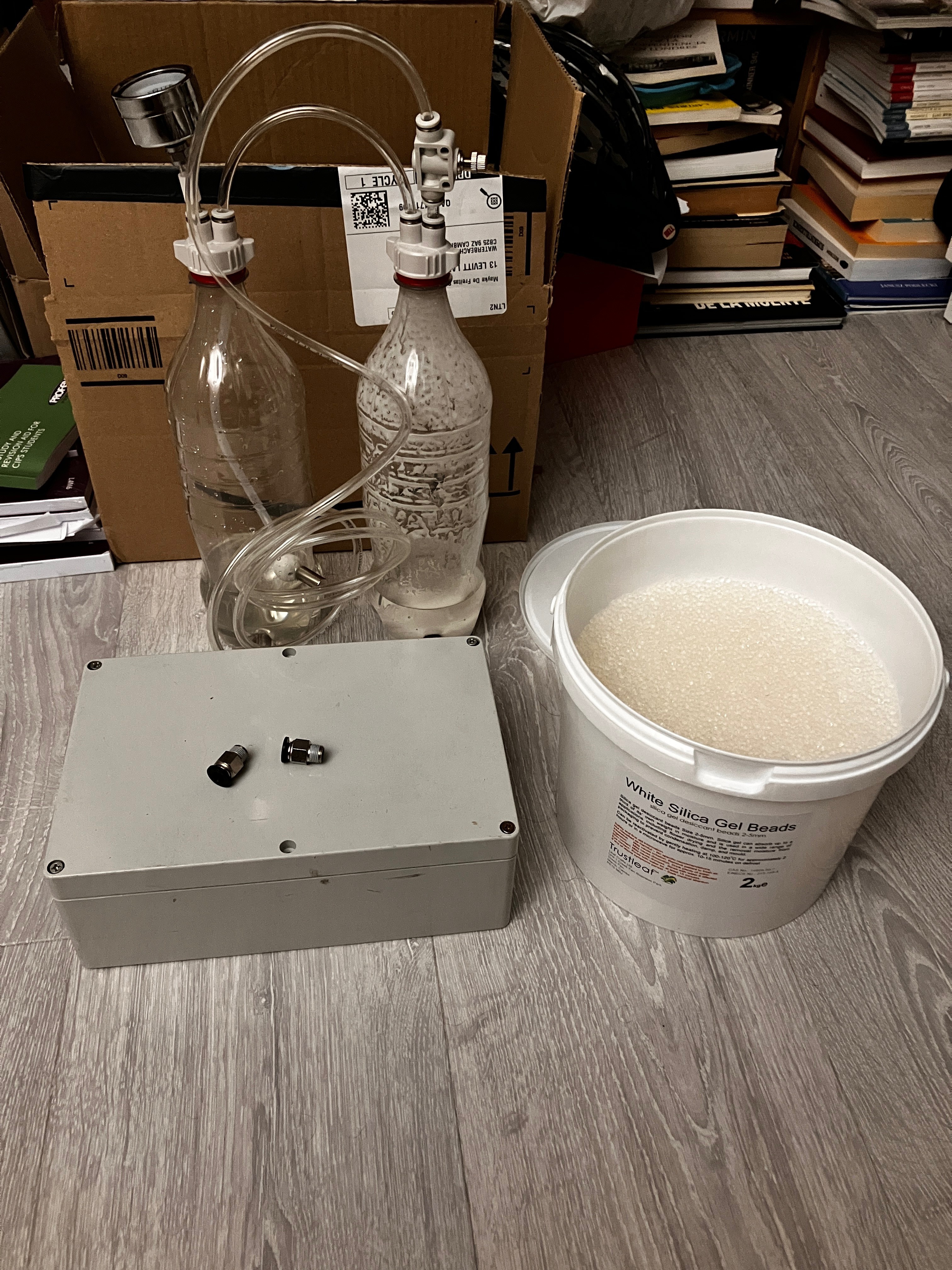

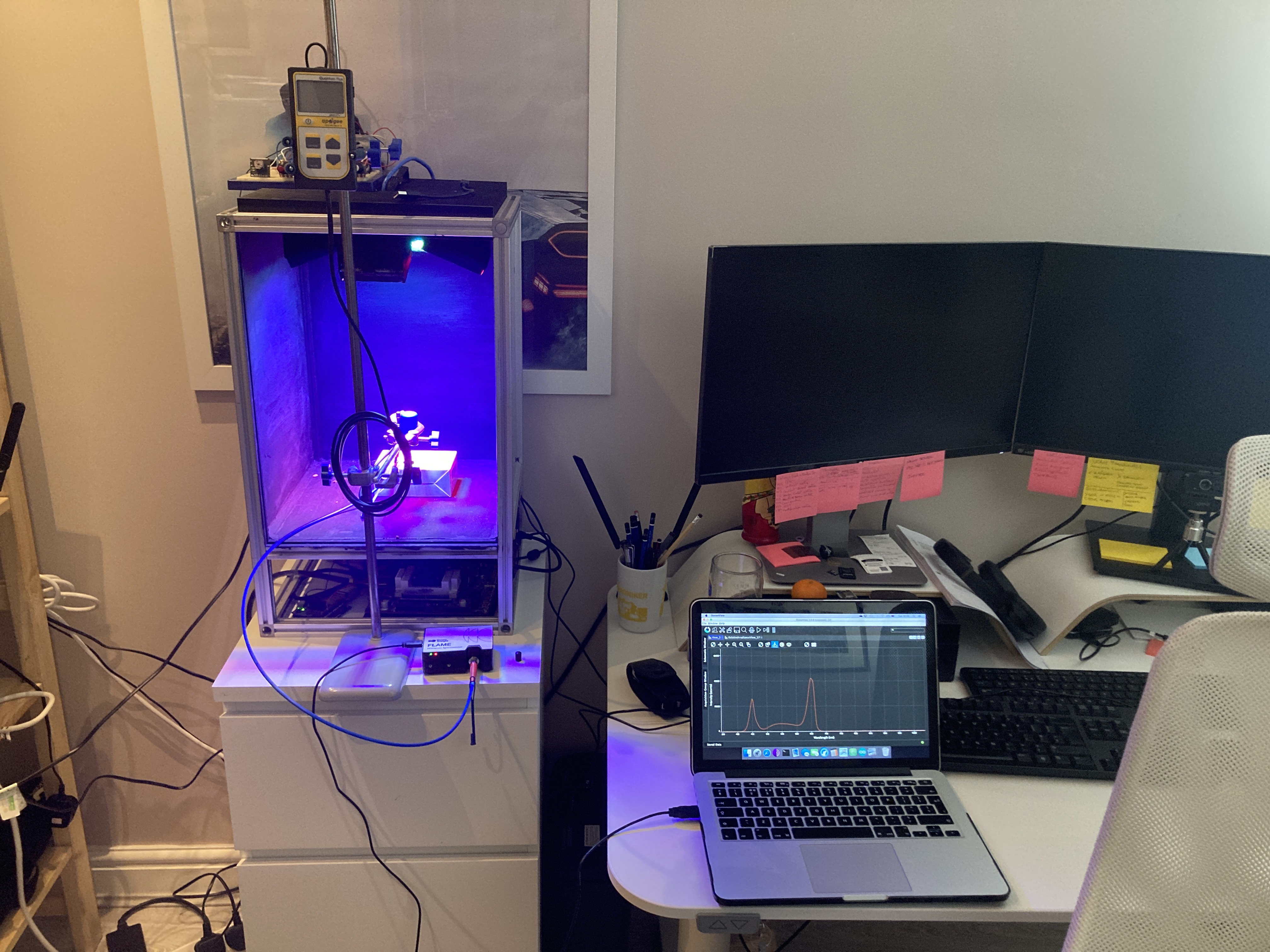

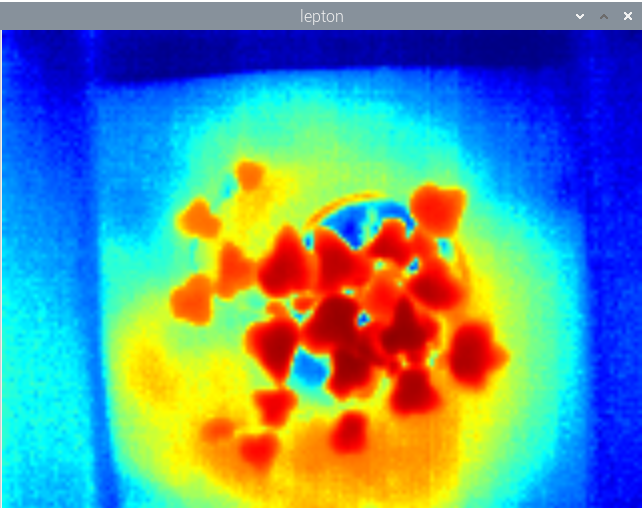

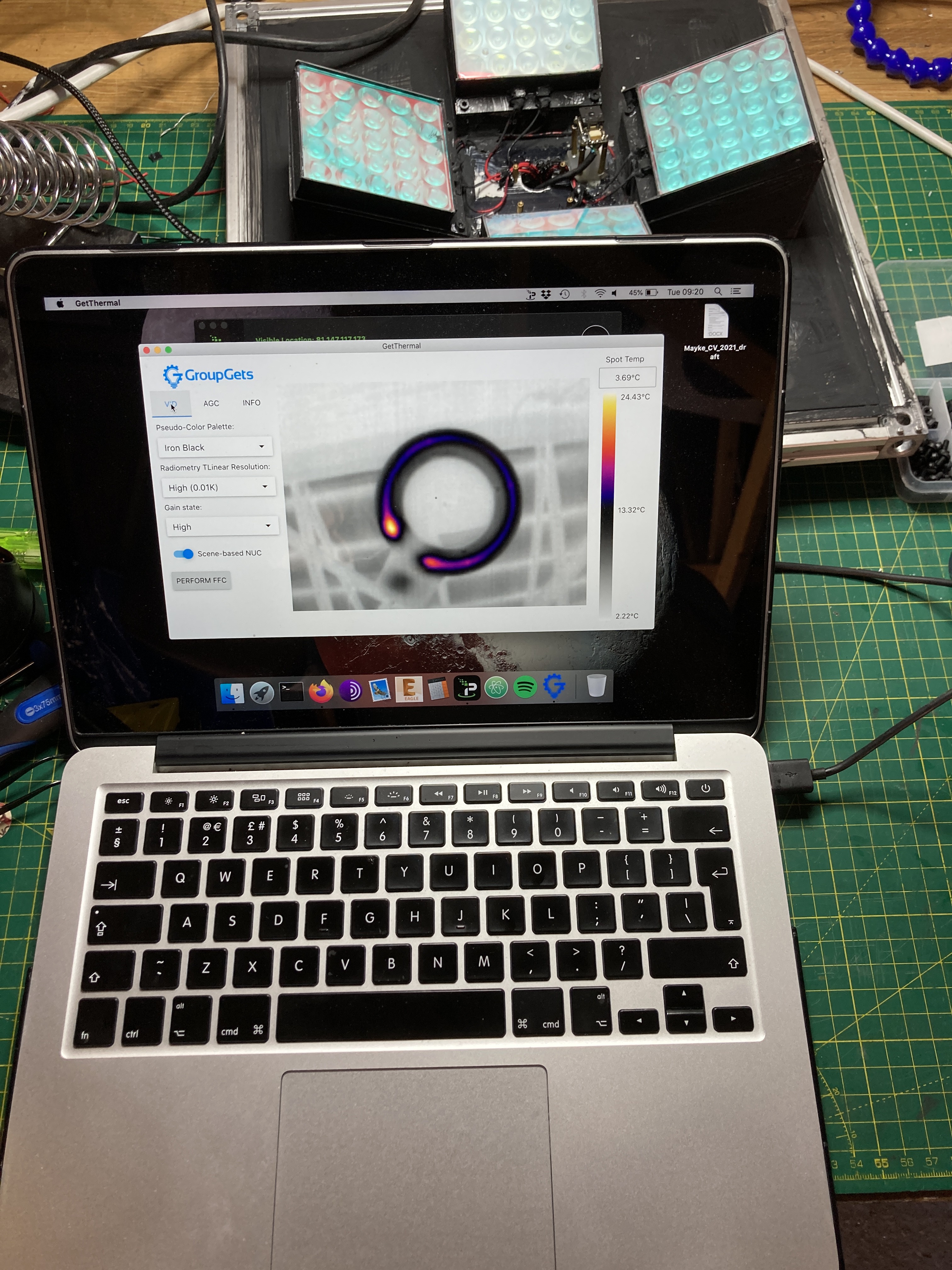

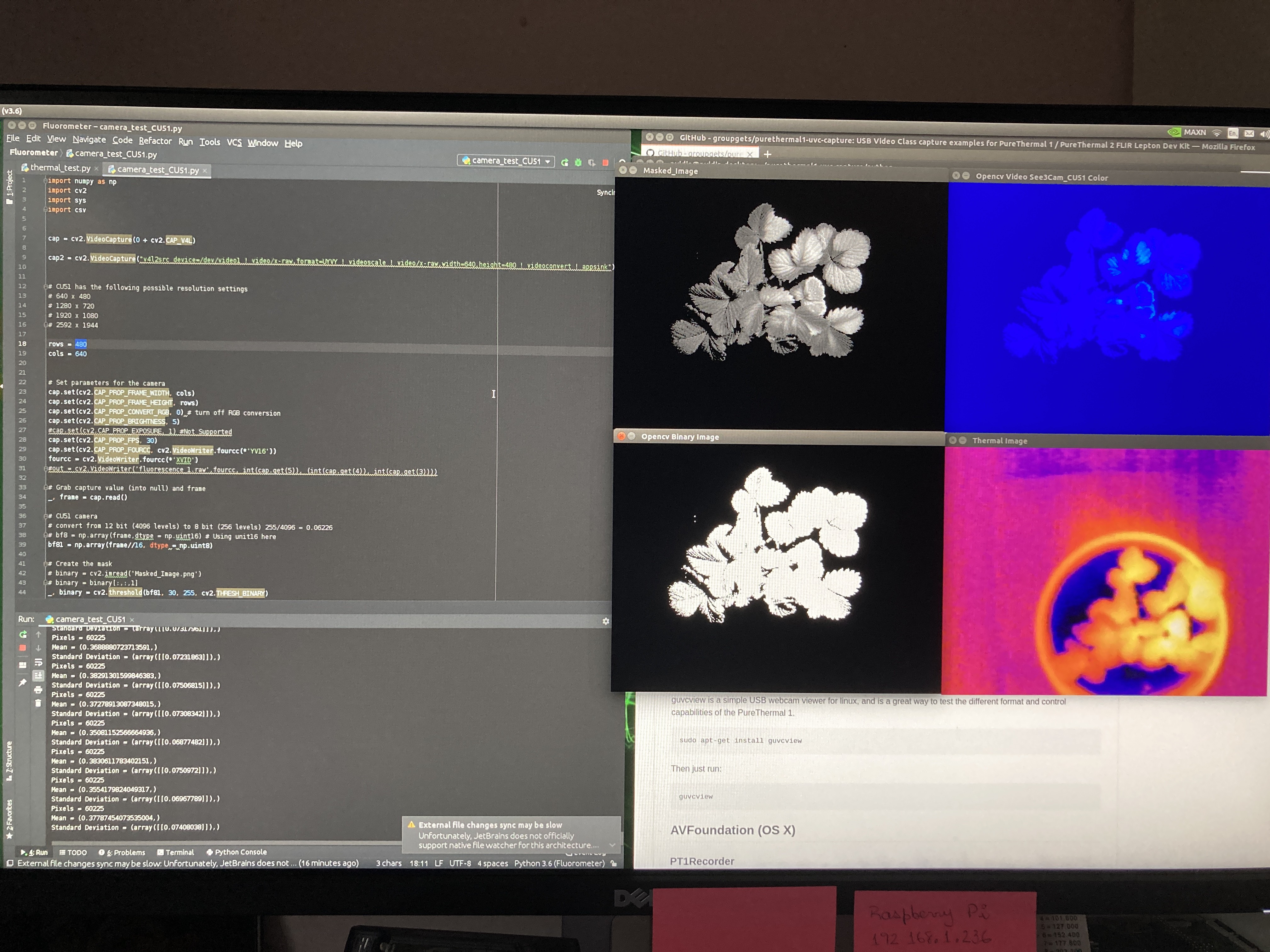

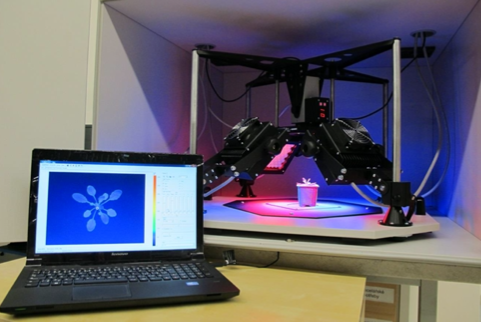

The idea of having an imaging fluorometer at home takes to a complete new level those of us with a keen eye for plants. Imagine, for instance, that you want to develop a more efficient LED lamp for your specialty crop, or that you are looking for ways to understand the underlying causes of stress under different external conditions such as lack of, or too much, humidity, extreme temperatures or lack of nutrients. But what does it make fluorescence to be above other well stablished techniques such as multispectral or hyper spectral imaging and/or ground sensors?

In order to answer the above question, we would have to lay some of the fundamentals about fluorescence first.

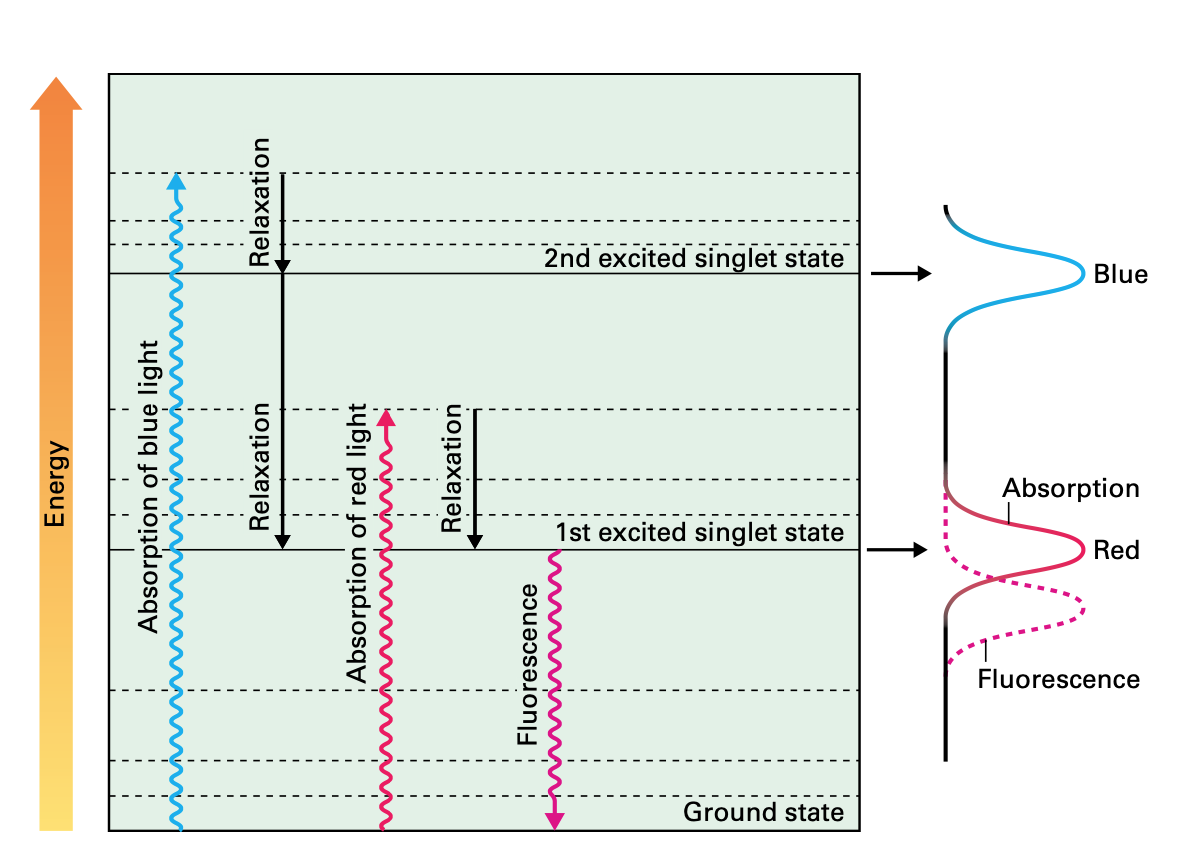

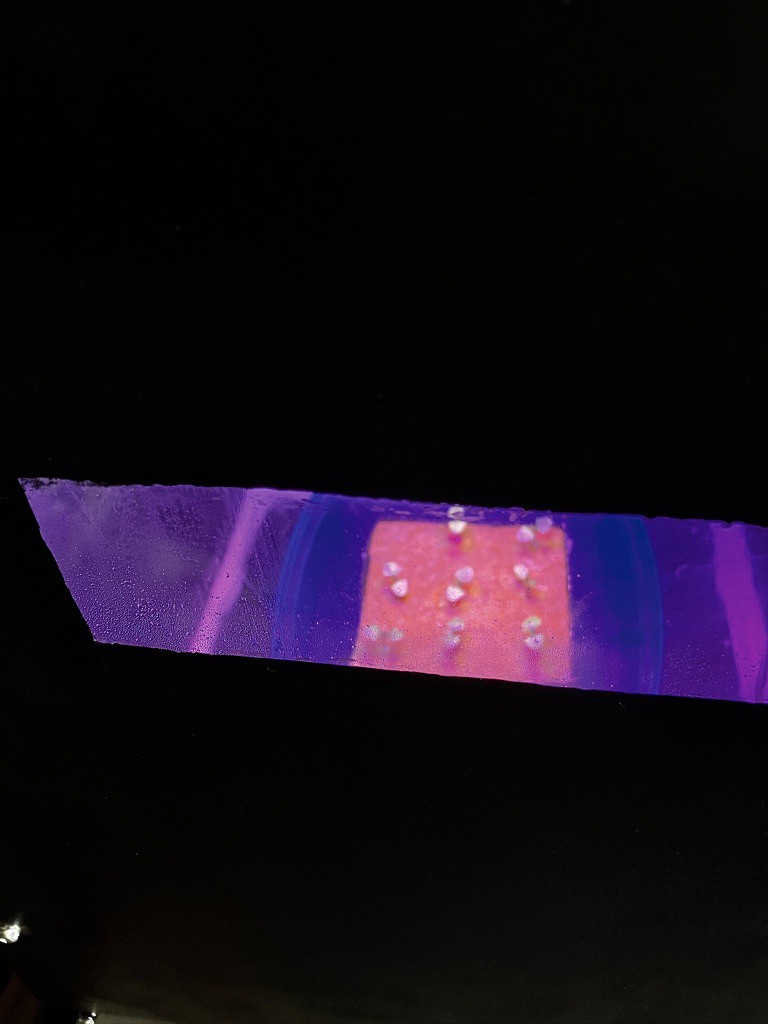

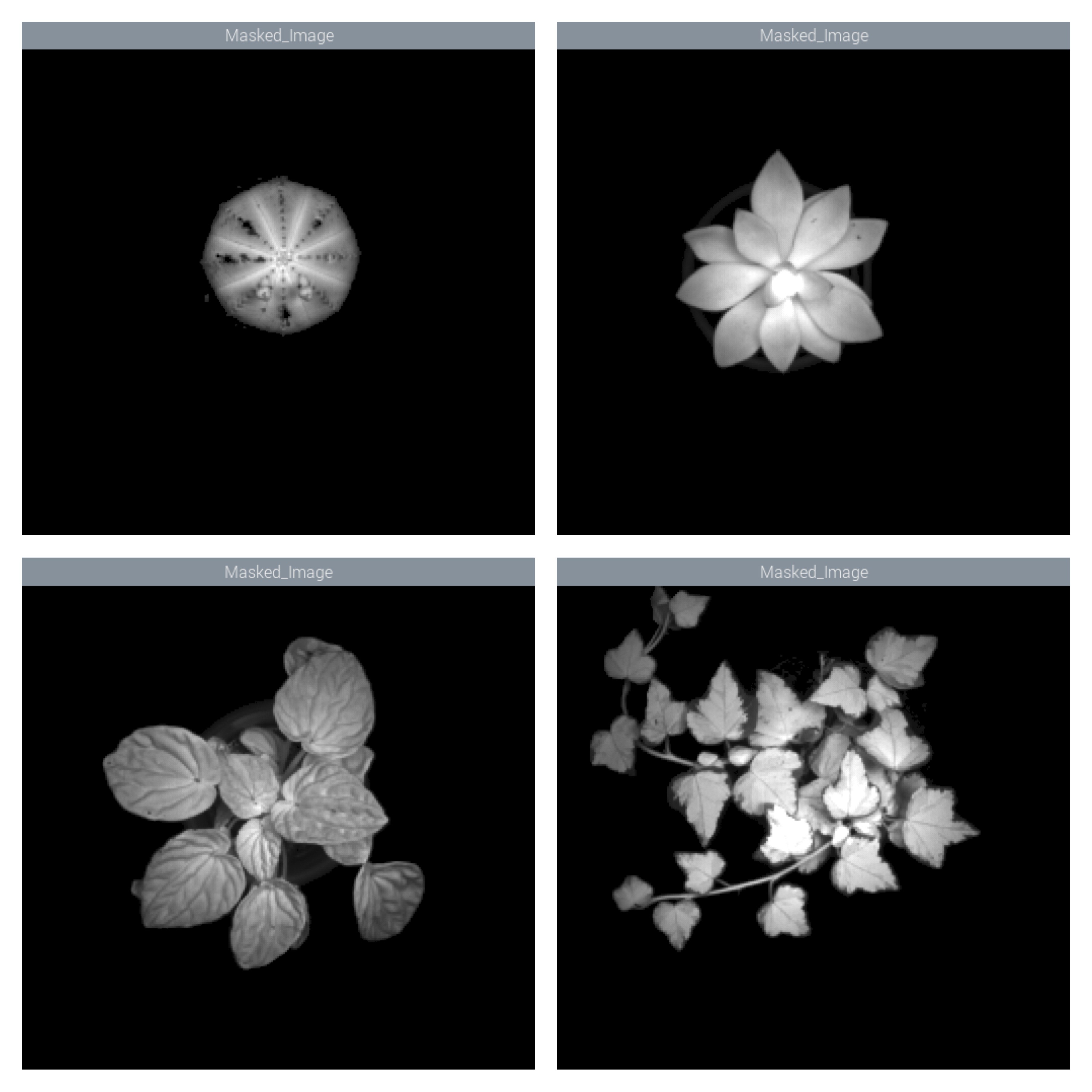

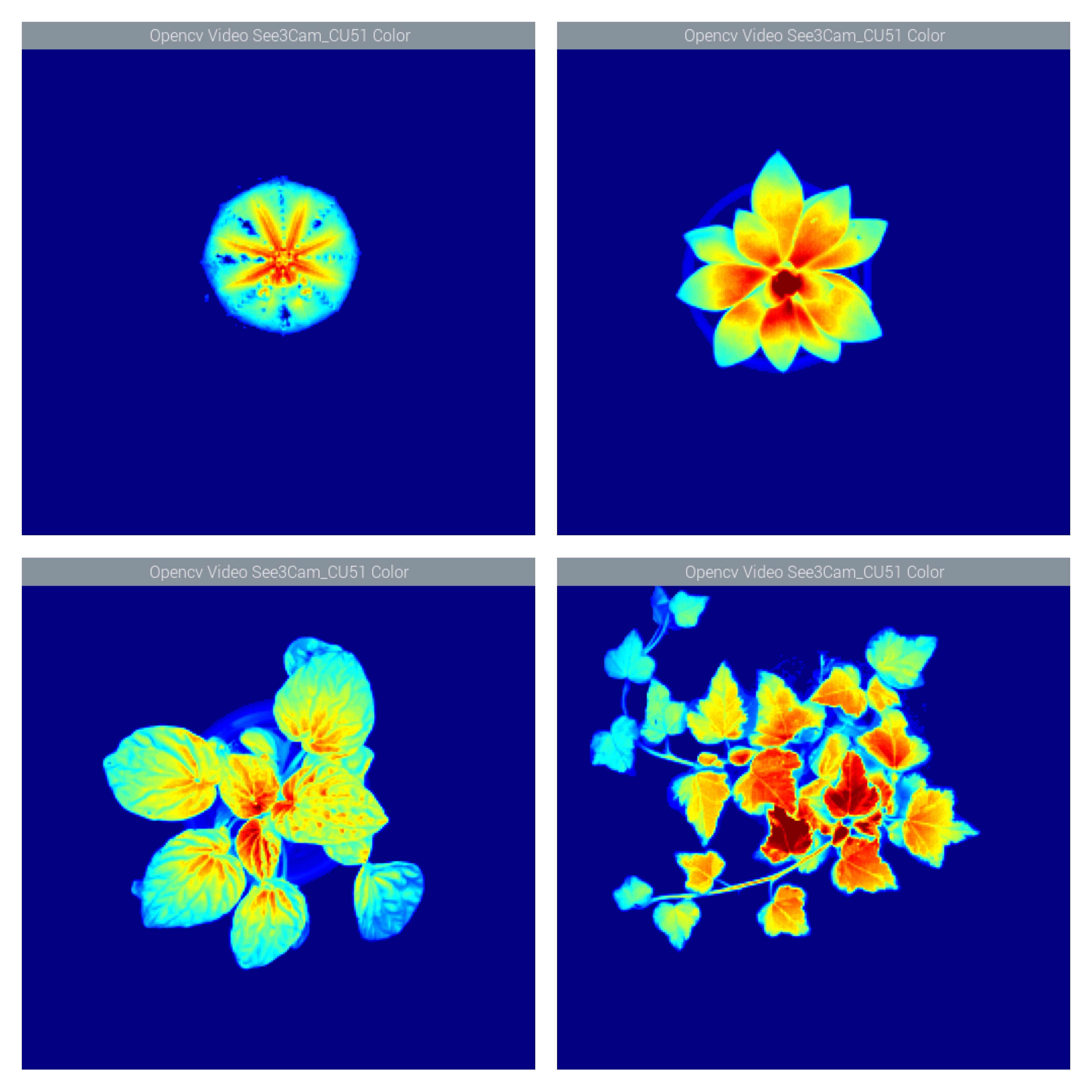

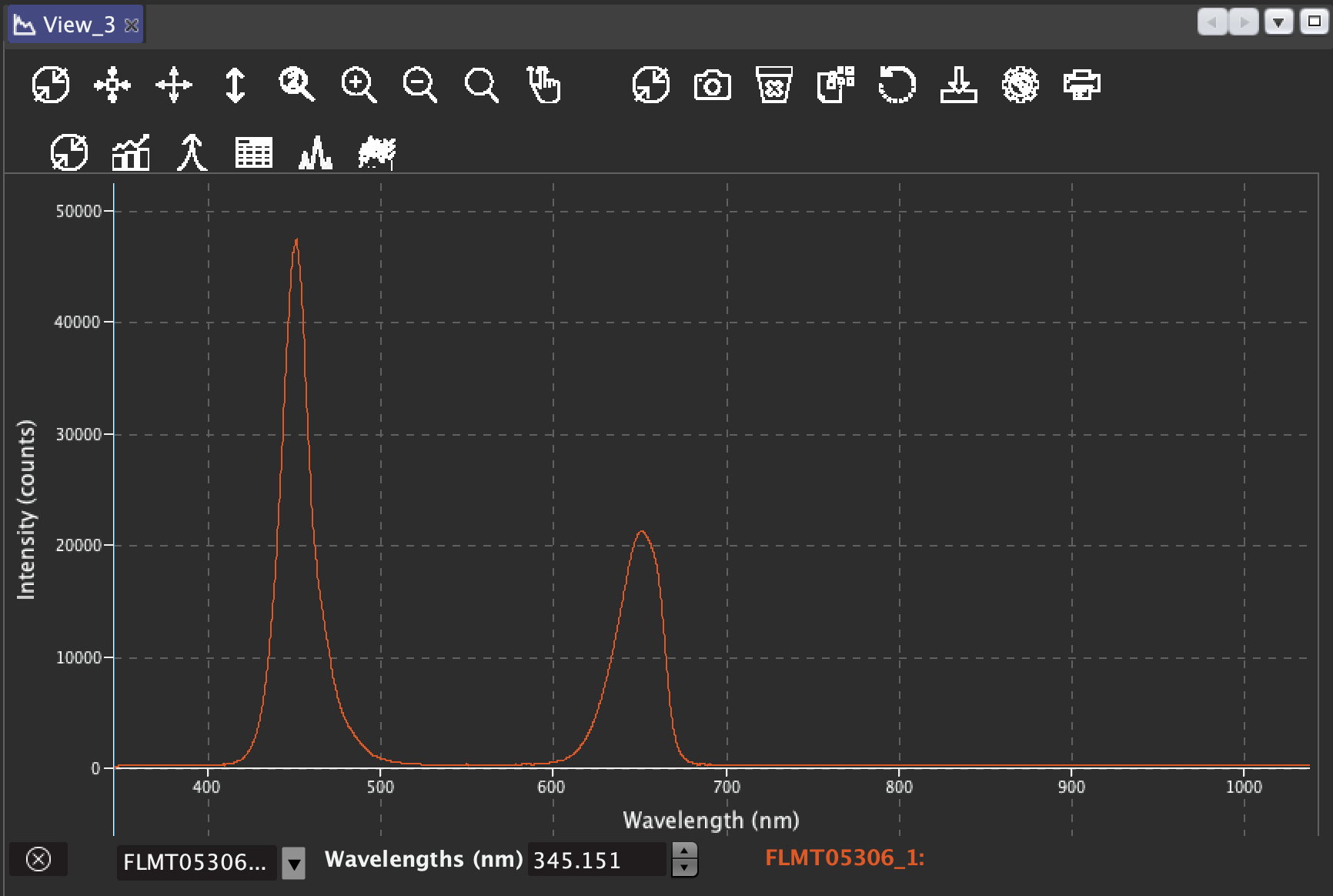

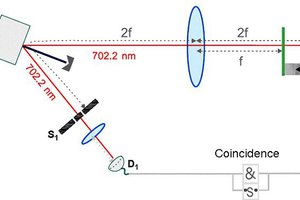

When photons reach the surface of a plant, they make the molecules of chlorophyll to get 'excited'. Literally, excitation means that the molecules absorb electromagnetic radiation from the UV-visible range of light, making the electrons to jump from a ground energy state to a higher energy state (See image below). Now, classical biology tells us that those ‘excited’ electrons will travel through other nearby Chl molecules by virtue of FRET (Föster Resonance Energy Transfer) until they reach the Holy Grail of the Light Dependent Reactions, that is, the Reaction Centre (CR), where they will finally get knocked off from the Chl molecules and transferred to the acceptor Plastoquinone. Let us bear in mind that Chlorophyll has two major absorption bands and therefore, it has two different energy levels other than ground: 1st excited singlet state (occasioned by red light absorption), and 2nd excited singlet state (a higher energy level attained from absorbing blue light, which is more energy intensive).

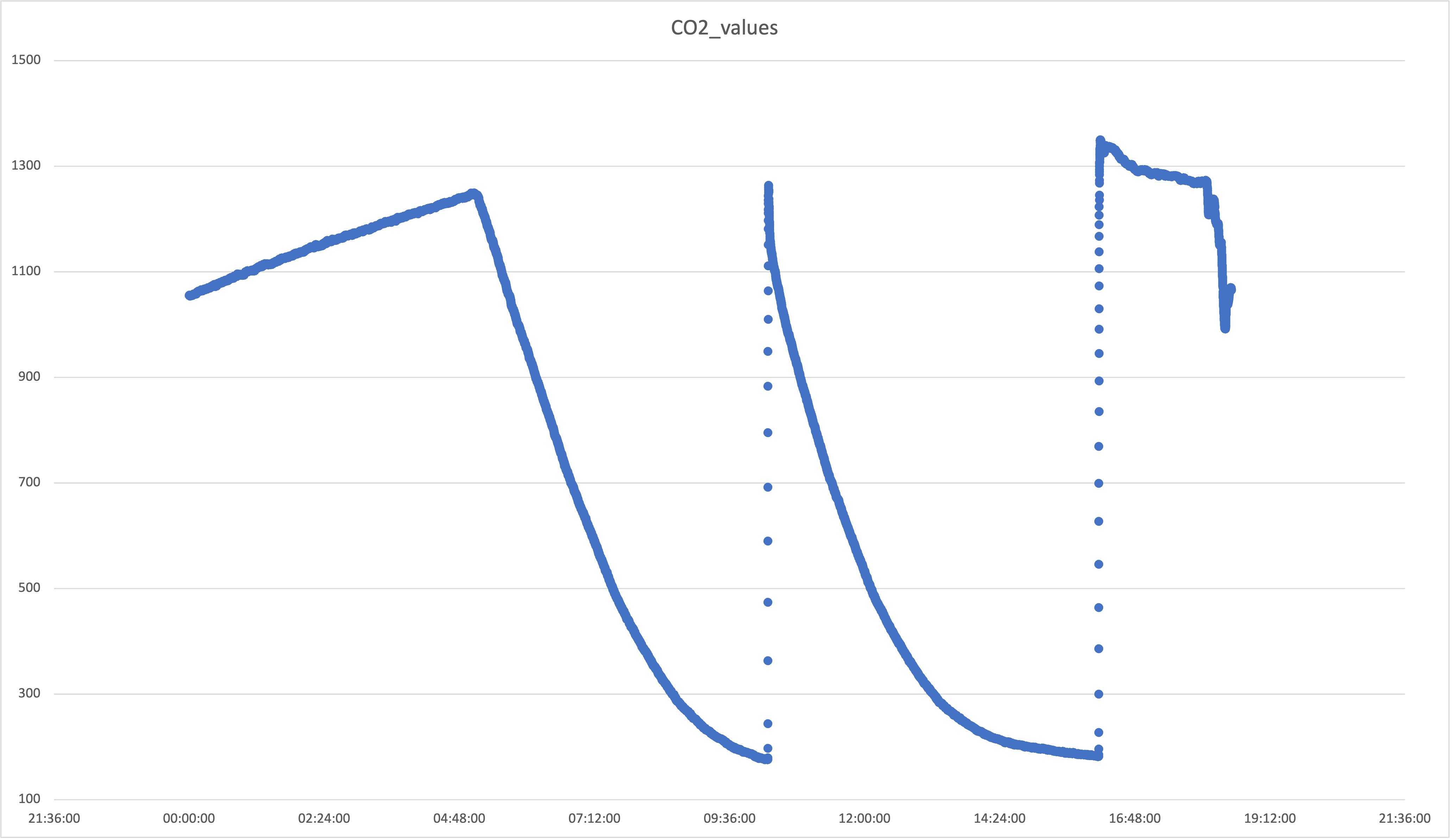

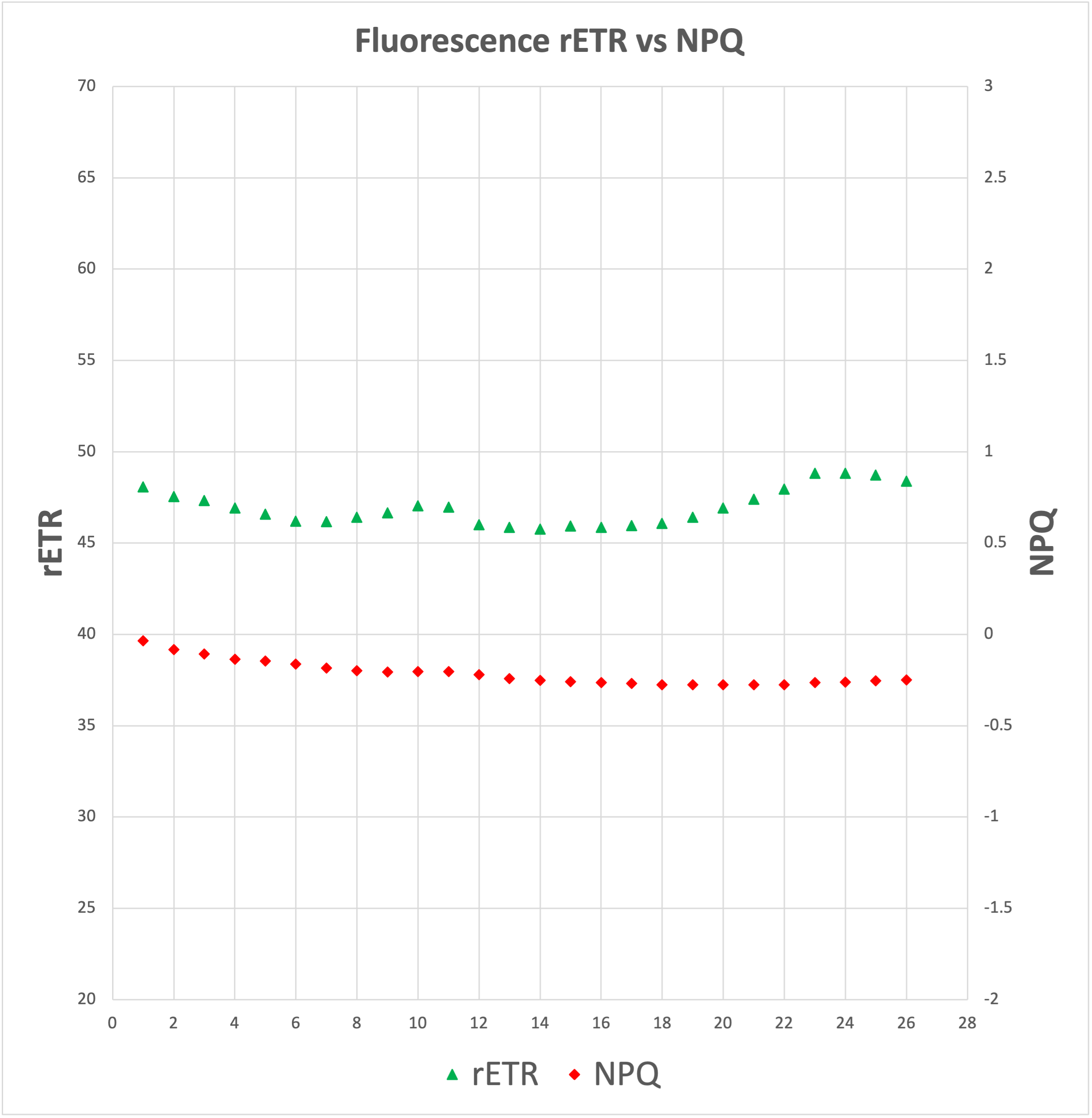

During this process, some of the energy produced by the excited molecules will necessarily be lost; as is the case when the amount of energy absorbed by Chl molecules exceeds the light utilisation of photosynthesis; such excess of energy is dissipated as heat as part of the Chl molecules returning to their ground state. Heat dissipation is always the result of vibrational relaxations that arise from the second excited singlet state. This photo-protective process is called Non Photochemical Quenching (NPQ).

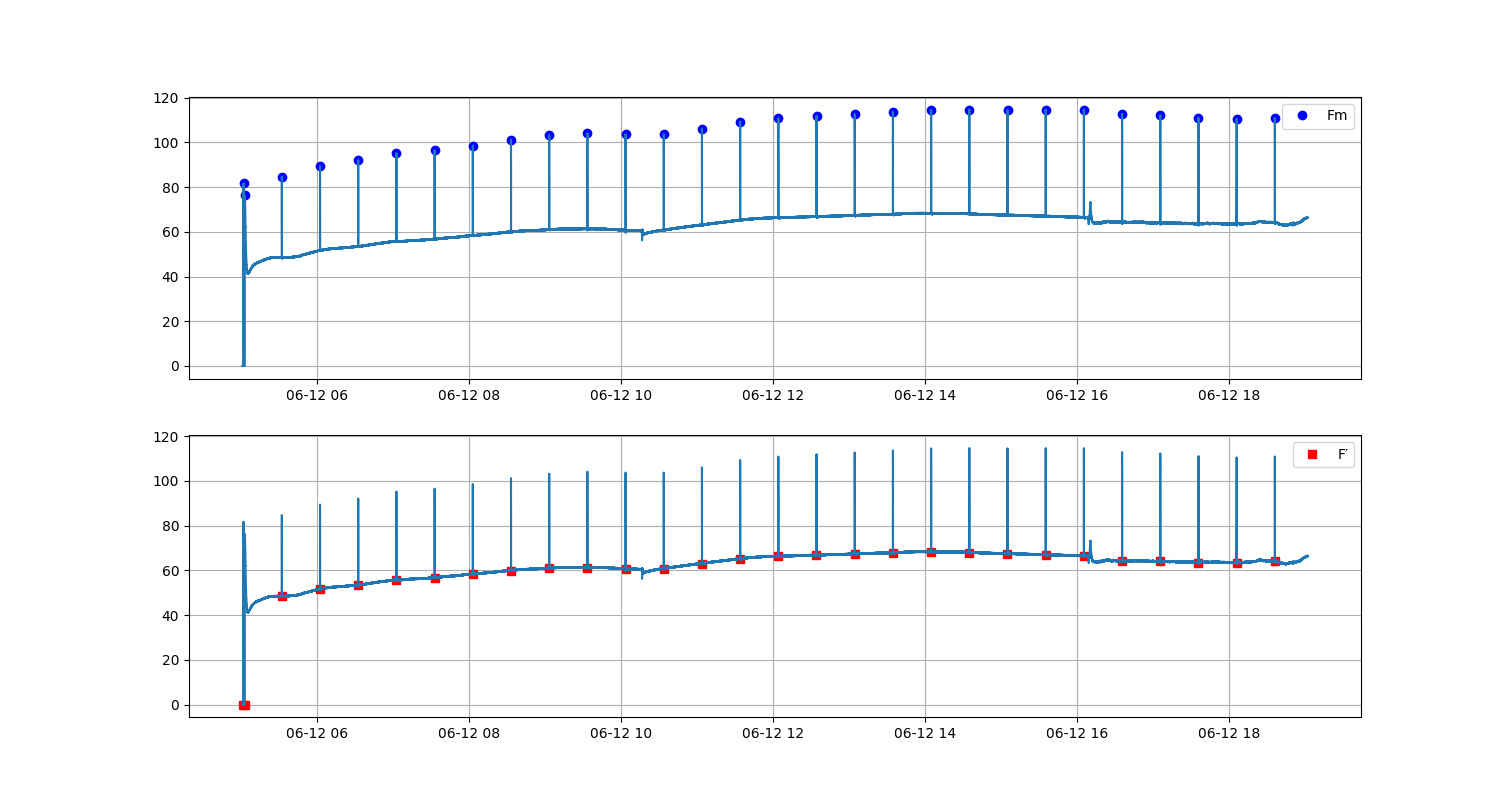

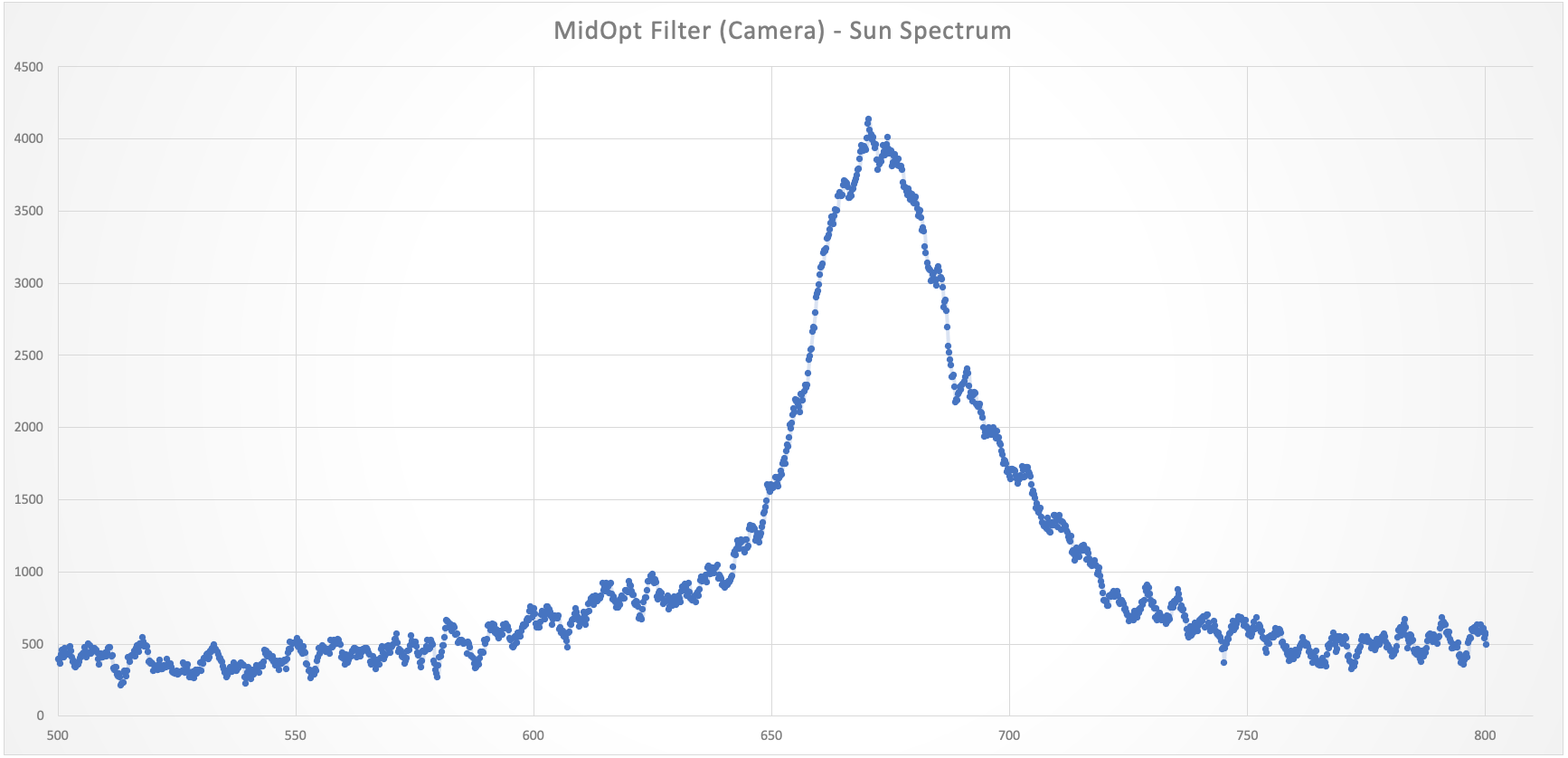

But heat dissipation is not the only way in which a Chl molecule can return to the ground state. Another mechanism involves the emission of a photon while the Chl molecule decays to ground state. Such emission is the result of decay from the first singlet state, and it has a longer wavelength (it will always be in the red portion of the visible spectrum) than the absorbed light. This final process is called fluorescence.

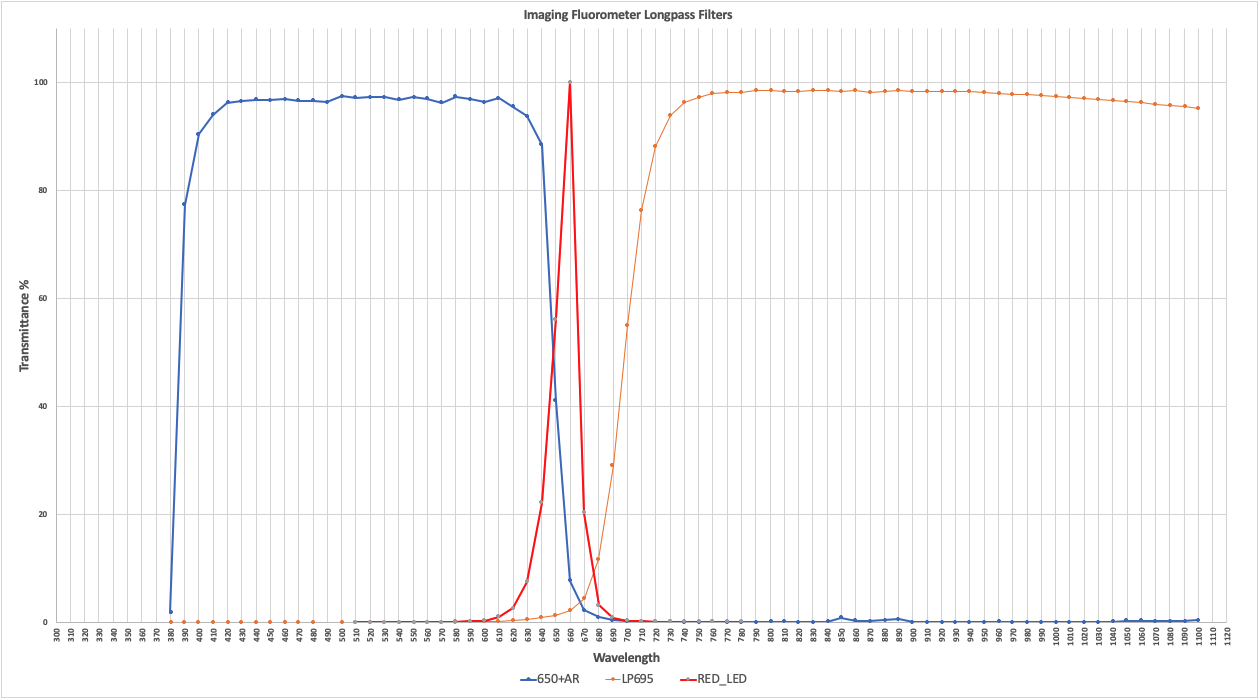

Now, the three processes, electron transfer, heat dissipation and fluorescence, occur against one another, which means that out of 100% of energy being captured by the Ch molecules, more or less 80% will be transferred to the RCs, around 18% will be dissipated as heat, and around 2% will be release as fluorescence. Any increment in any single one of them will mean a reduction in the other two.

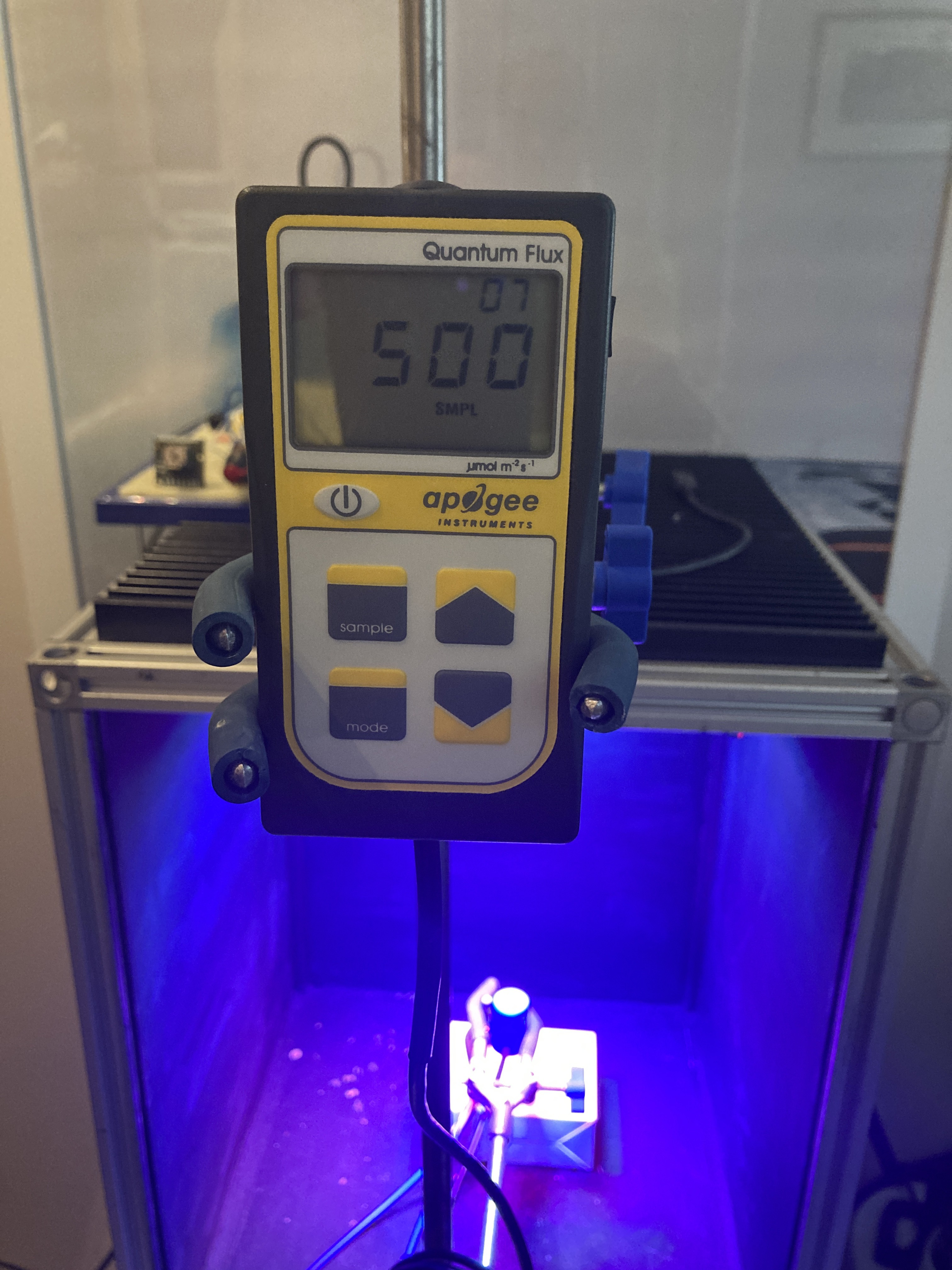

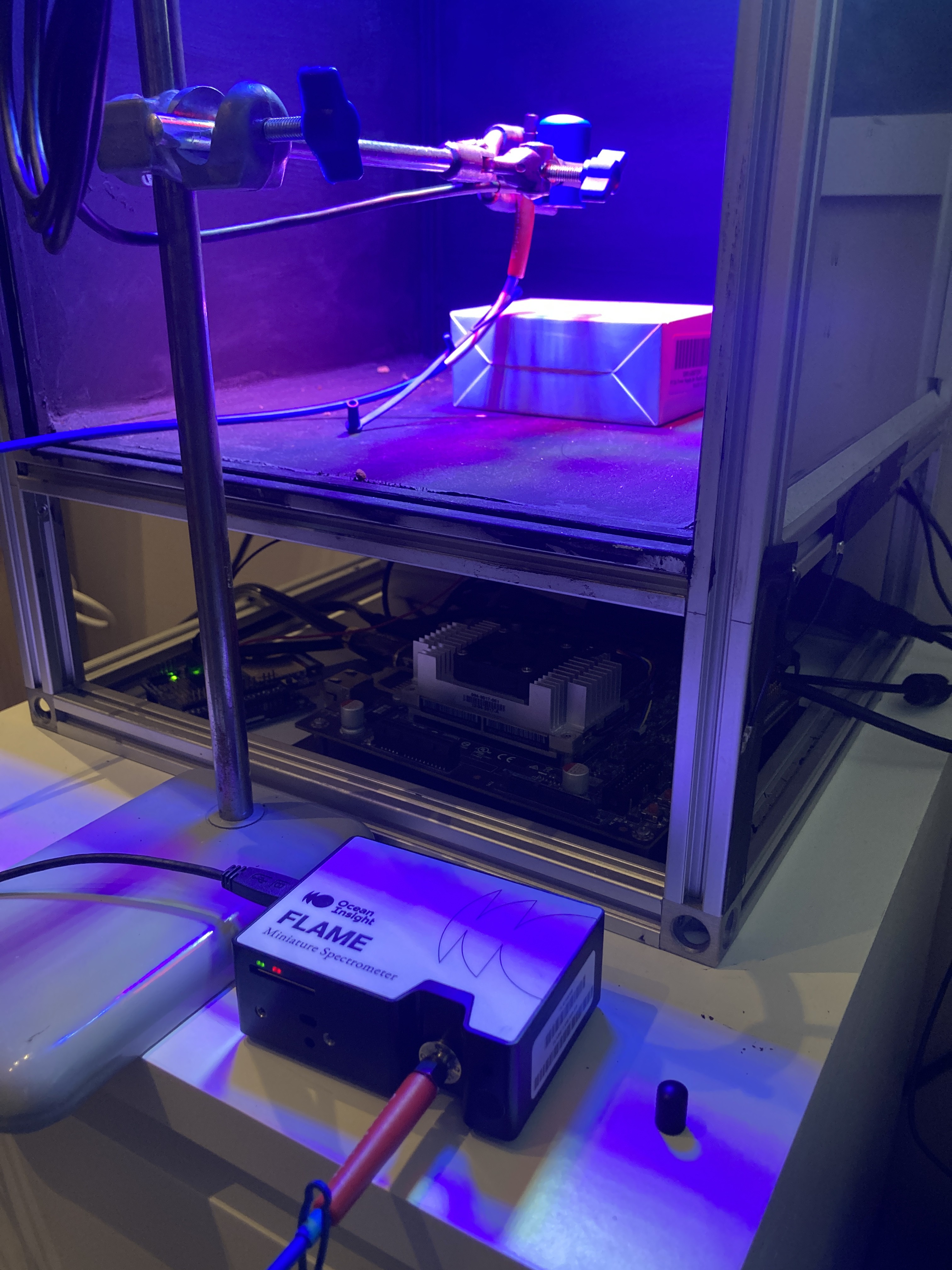

The above has huge implications when studying plants, for one thing is to measure external factors such as light intensity, humidity levels or nutrient content, and another one completely different is to be able to know exactly how many electrons are being used by a plant to sustain glucose production. At the heart of measuring Chlorophyll fluorescence is the examination of photosynthesis performance, the single most important process occurring inside a plant.

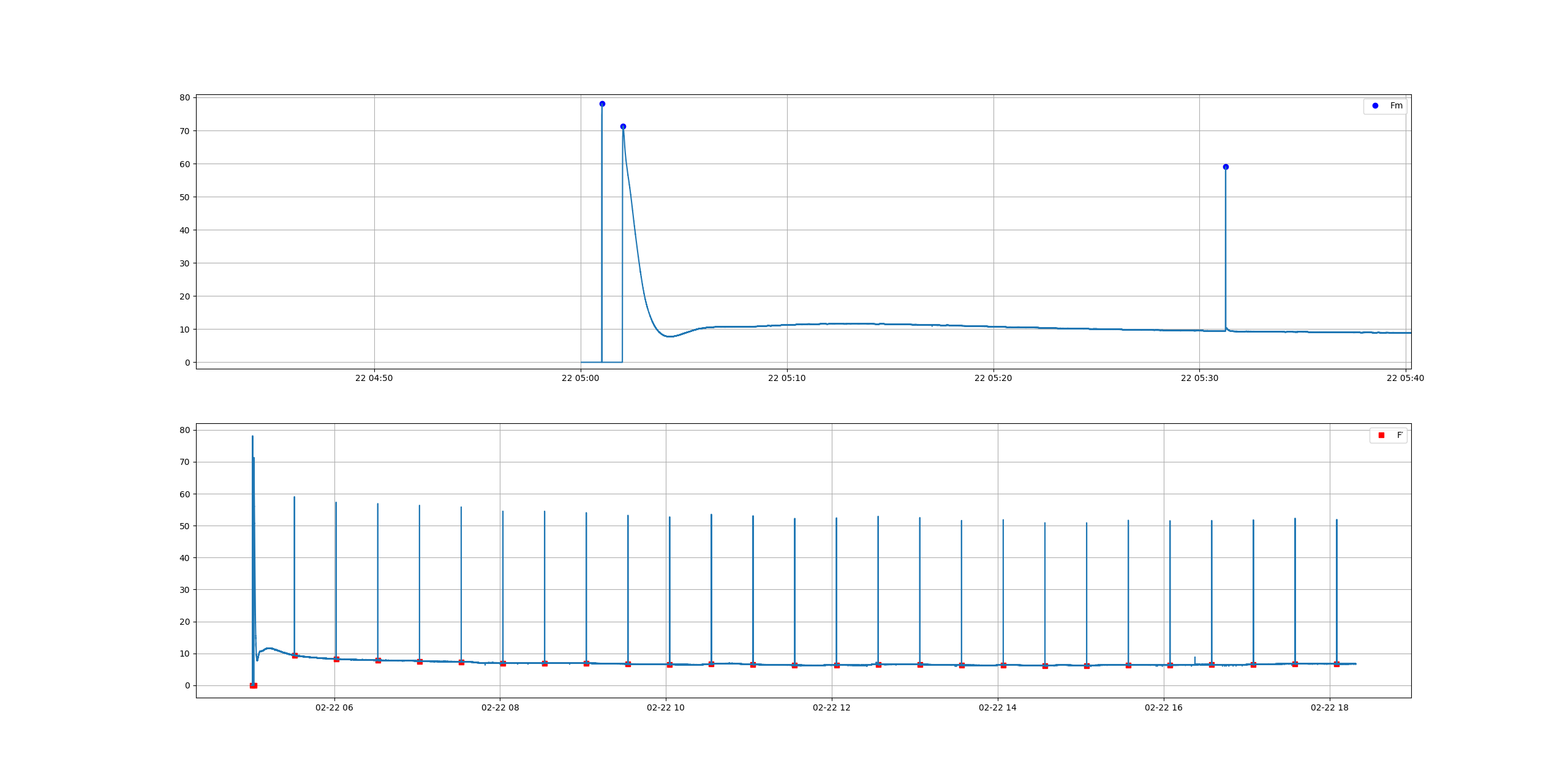

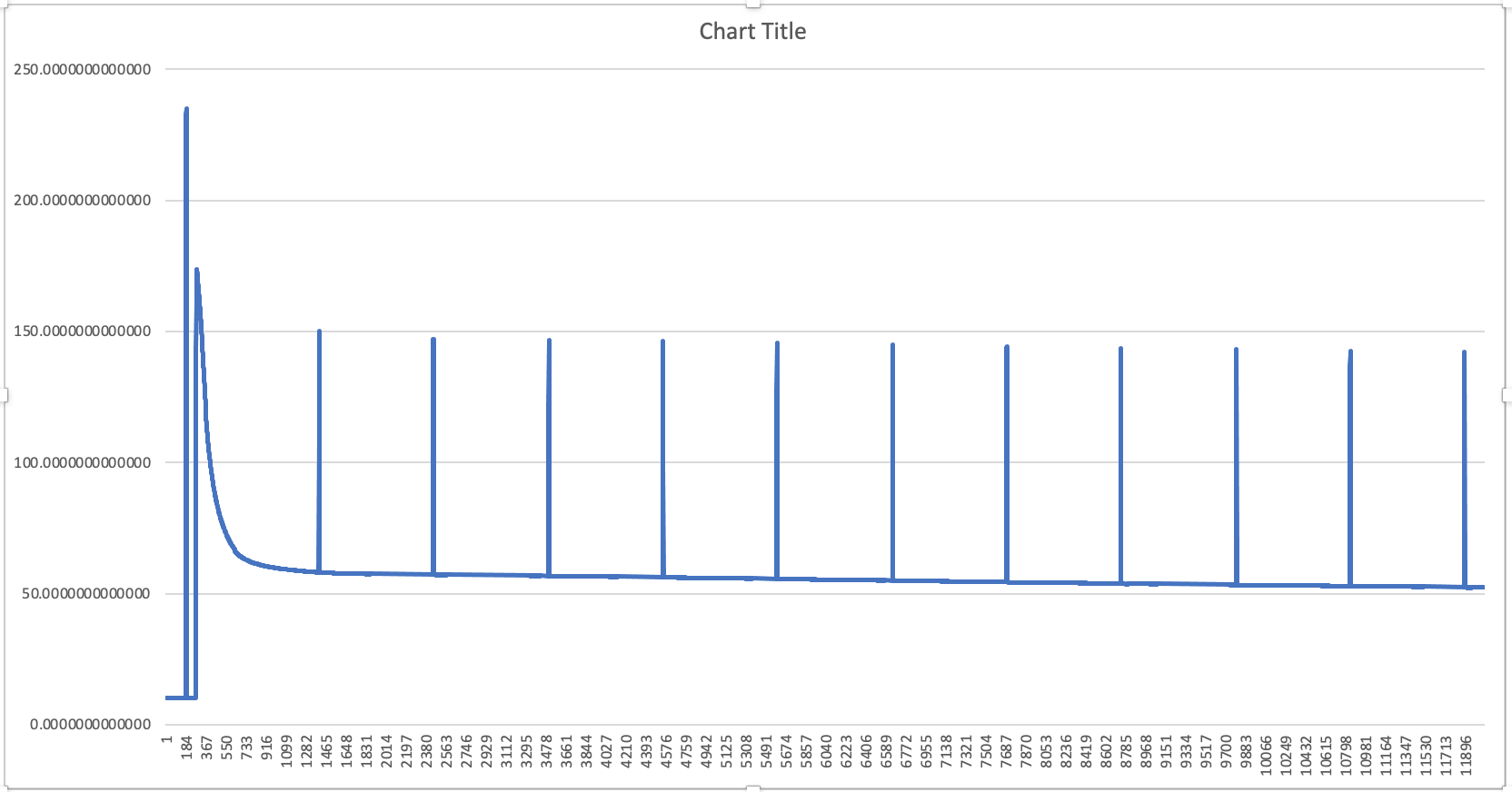

Kautsky & Hirsch Effect

In the early 1930s Professor Hans Kautsky and his collaborator A. Hirsch observed an increase of fluorescence intensity when dark adapted photosynthetically active samplea were illuminated. They published their discovery in Naturwissenschaften with the title Neue Versuche zur Kohlensäureassimilation...

Read more » Mayke

Mayke

jupdyke

jupdyke

Ben Hartmann

Ben Hartmann

Jovan

Jovan